|

Dawn Chapman is Primary Programme Lead for ITT Exeter Consortium and Exeter Teaching School Alliance

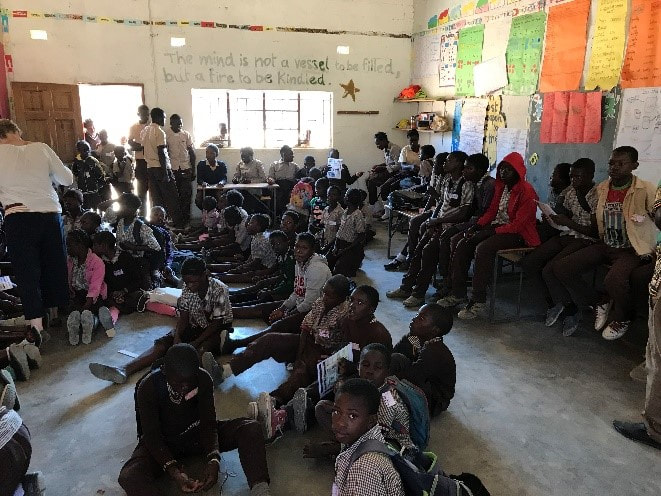

As the washing machine whirls away working on the suitcase of filthy clothes I have brought home, I can reflect on another valuable experience teaching and working with teachers. Last week I was lucky enough to be released by our Teaching School Alliance (TSA) to work in a charity school in Zambia. I was accompanied by my colleague, Carrie McMIllan, who leads South West Teacher Training, the SCITT we partner with to deliver our primary initial teacher training (ITT) programmes, along with our amazing administrator Louise Honan, without whom we would have been lost (possibly in the African Bush). We went with our TSA vision in mind – schools supporting schools – and were very grateful to be able to support and learn from this inspirational school and its teachers. The school is Nayamba School (http://nayambaschool.org/), a charity school built on a farm in rural Zambia by the farm owners in order to give education and opportunities to the children of the workers. Without the school, the children would have no education as the farm is too far from any state primary school. The school has a food programme which provides children with a hot nutritious meal every day, and also provides monthly bags for the girls so that they can attend school when they have their periods. Each year a team of teaching volunteers visits the school and the aim is to support the teachers in continuing professional development (CPD) and to support them as they strive to deliver the best education to their children. This year, we went to release the teachers to have sexual health CPD in the school, which they then delivered to the children and members of the community. HIV and hepatitis is a huge problem in Zambia and many of the children have lost parents and other family members as a result. We took suitcases of useful resources, taught classes and collaborated with the teachers. Teacher training is far more basic in Zambia with little school-based practice (if any) and therefore the teachers are always keen to learn from, and work with, the visiting teachers and are incredibly open to advice and support. Having visited three years ago, I was delighted to see the development of the school; not just the buildings and resources (running water, proper toilets and whiteboards – rather than blackboards), but the development of teaching practice. Teachers were more creative, were using manipulatives to support learning and applying techniques modelled by previous volunteer teams. Some of the lessons on the Zambian curriculum were a challenge for me. I’ve never taught a lesson to Year 1 before focusing on keeping safe from HIV and Aids. At times I felt like a trainee all over again, despite my 20+ years in the classroom. Children never fail to surprise you – while discussing the danger of sharing razor blades during our HIV awareness lesson, a child helpfully produced an unsheathed razor blade (used for sharpening his pencil) from his pencil case. Always helpful to have some concrete resources to hand. When I visited before I was a teacher in a primary school. This time I visited as a teacher trainer and it was an opportunity to reflect on the similarities of teaching and learning in this setting compared with a UK school. What are the lessons I could take back with me to share with my new cohort of trainees? In a classroom with only wooden desks, a teacher whiteboard, children with just a lined book and a pencil, the learning experience for children was in many ways very different from most UK schools. Often the teachers had to be creative about how to support learning given extremely limited resources: using sticks and stones instead of base ten apparatus. Over the course of the week, I had the luxury of observing the Zambian teachers teach as well as teaching their classes myself. We were also able to team teach. They struggled with the same challenges that teachers and trainees in our schools do. The Grade 2 teacher asked me how I manage to support children who find the learning harder than others in the class; how do I provide challenge and support to meet the needs of all children? These are questions which all trainees and teachers ask regularly. I didn’t have all the answers – who does? But I shared my ideas and we tried them out with his class. We weren’t completely successful; some children hadn’t grasped the objective by the end of the lesson despite my guided group (seated on the floor with bottle tops to demonstrate division by grouping), but the higher achieving children enjoyed and rose to the challenge of grouping a large number in as many different ways as they could. We put this problem in the context of the huge numbers of children attending the teacher’s craft club after school. Don’t ask – we’re still recovering. It’s clear: differentiation is hard, wherever you work and whatever your class size. It’s especially hard in an early years’ classroom with a large class, no teaching assistant and a high level of EAL…as many of our UK teachers and trainees will know. Obviously, I felt the challenge of teaching without the luxuries I’m used to: the internet, a photocopier, reliable electricity, a computer and all the many material resources we enjoy. Ensuring all the children had a pencil was a challenge at times. But conversely, it was strangely liberating. Without the interactive whiteboard and any other fancy resources, effective teaching came down to the nuts and bolts of our craft. And without the distractions of the developed world classroom, it was possibly clearer to identify. Like most training providers, Exeter Consortium and South West Teacher Training are committed to reducing workload for our trainees, focusing on what really matters in the classroom and reducing all the unnecessary burdens which have become a pressure on our teachers. Nayamba showed me what really matters. Good teaching looks the same in Nayamba as it does in the UK. Knowing your children, giving clear instructions, breaking learning down, modelling, using visuals and concrete resources, employing effective strategies to assess and move children on or support learning. I saw phenomenal progress in some lessons – from pupils being taught in English which is not their first language. The best teachers revisited prior learning, chunked learning, gave students many opportunities to practise, questioned to check for understanding and had to regularly think on their feet, rather than sticking to the plan they had written. They were incredibly committed to developing their practice: reflecting on their students and their lessons and asking other teachers for advice. There was no fear that they would be judged for not knowing the answers. So, now the African dust has settled, what do I take away from this week? One of the key articles we share with our trainees is Barak Rosenshine’s “Principles of Instruction”. Strip away all the trappings of our first world classrooms and you can see what makes teaching effective. Barak’s paper summarises them clearly. That is what we share with our trainees and what we ask them to focus on. That, and the desire to make a difference and the confidence to ask for help when it’s needed.

0 Comments

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed